Here’s a voiceover of today’s post.

Welcome Back

Hello again friend! So glad you’re here :)

Here’s what we’ll cover today:

Our imaginations are muscles and they need to be exercised. Design fictions are a tool to grow imaginative capacity

The Rubber Band Effect might be trapping us in the polypermacrisis — and what Star Trek and The Black Panther have got to do with getting us out

An invitation to live long and prosper

Two bonus sections with 20+ tools and resources for growing imaginative capacity and 4 directories of Substackers working on futures worth living in.

Beam us up, Scotty. 🖖🏼

Students From The Future

I learned about speculative design and design fictions from a group of Change Lab students — the social innovation course I taught at Simon Fraser University that I told you about in The Permissionless Prof’s Origin Story.

When we workshopped their final project, the group explained they wanted to make a series of design fictions about SFU’s sustainability practices.

I didn’t initially understand what a design fiction was, but it clicked when they shared the Star Trek example.

Design Fiction: A design practice that brings possible futures to life.

By creating stories, objects, or videos from an imagined world, they help us suspend disbelief, reduce cognitive dissonance and explore what could be. Its purpose is twofold: first, to explore the social and ethical implications of today's emerging trends or technologies; and second, more radically, to expand our imaginative capacity to build worlds we can’t yet see.

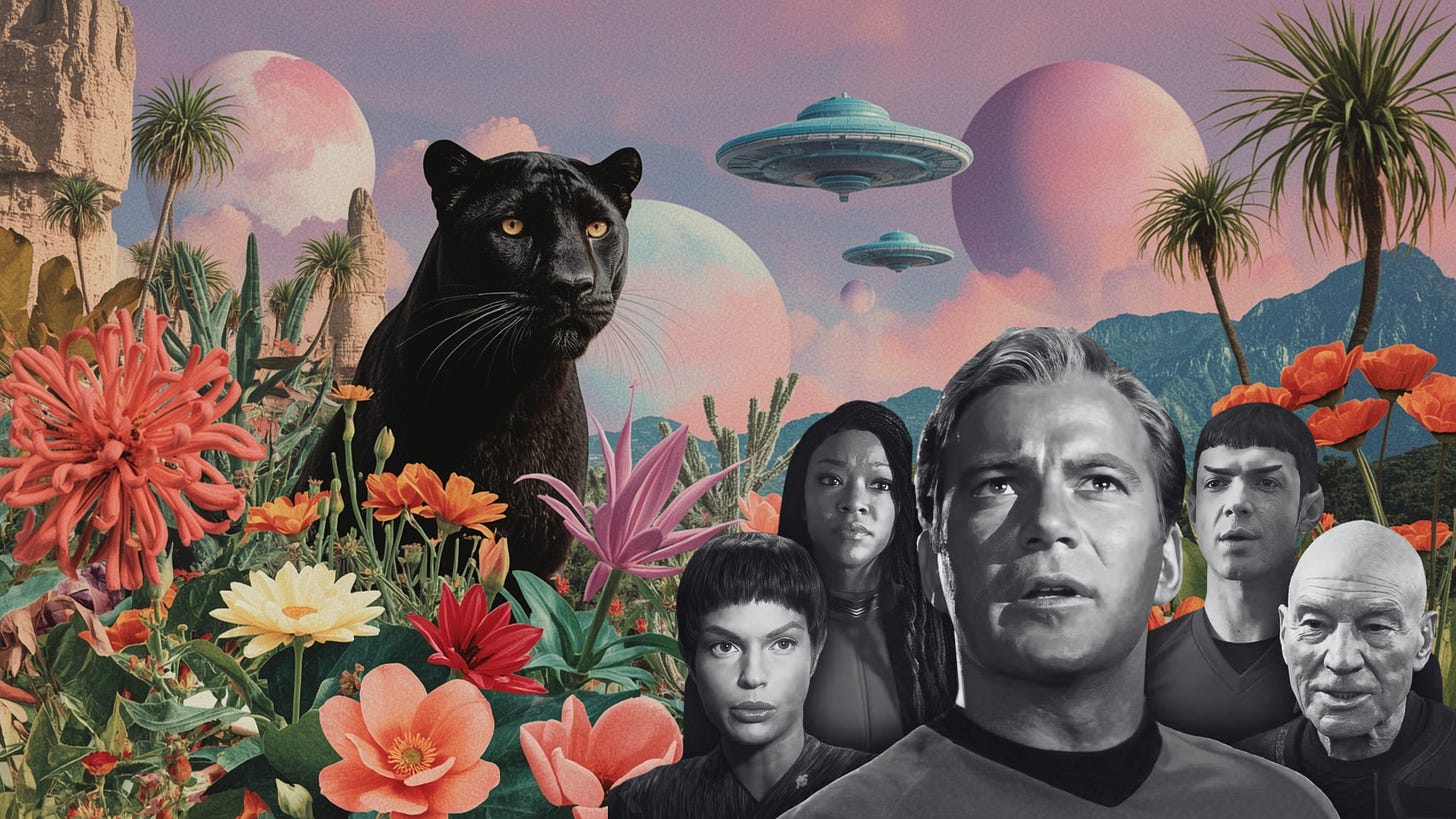

Some design fictions are crafted intentionally; others (like Star Trek) are existing works we treat as design fiction when they inspire us to ask “what might this world feel like?” Science Fiction remains the genre most closely associated with the practice, offering both inspiration and narrative tradition.

Star Trek is perhaps the most famous example of a design fiction, having directly inspired many of the most consequential technologies we take for granted some 60 years later.

Communicators → cell phones and video conferencing

The holodeck → virtual reality

The LCARS computer on the Galaxy-Class USS Enterprise D → Google and conversational A.I.

The LCARS interfaces throughout the Starships → touch screens

NASA even named the first US orbiter Enterprise and William Shatner became the oldest person to ever go to space on a Blue Origin rocket because Jeff Bezos is a lifelong trekkie.

The sci-fi future Star Trek beamed us to wasn’t just entertainment.

It was imaginative capacity.

And imaginative capacity these four students1 were not short of. I certainly learned more from them than they learned from me that semester.

Imaginative Capacity: the fundamental, uniquely human ability to envision that which is not yet real.

It is both an innate right — the power to dream the future for ourselves — and a cognitive muscle that grows stronger with exercise. This capacity is the wellspring of invention, innovation, and empathy, allowing us to connect with experiences we have never shared. In a world dominated by established narratives, it serves as a revolutionary tool to decolonize our minds, break free from being trapped in someone else's story, and reclaim our power to see and create new possibilities.

Their work was so good in fact that we got a letter from the university asking them to edit or remove the videos because the branding made them look too official.

There are six videos in their series. I recommend them all. They’re set in 2065 in celebration of SFU’s 100th anniversary and tell the story of a radically sustainable campus.

A Poverty of Imagination

Design fictions weren’t the only consequential thing they taught me that semester. Kashif — who played the fictional president of SFU 2065 — introduced me to the book Winning The Story Wars by Jonah Sachs. It explains how social media restored (digital) oral culture at scale making compelling stories what matter most.

Stories, fundamentally, are about the capacity to imagine.

And capacity to imagine might be the most critical capacity of our Now/Future.

Humans are reliably shitty at doing that which we cannot conceive.

Our minds have been so thoroughly colonized — and I mean that literally and politically — that not only do we have trouble imagining outside of the very scripted, curated, thoroughly reinforced version of reality as we experience it today, but we almost as a rule, automatically reject that which we cannot see.

Seeing is believing.

“…what drives our machines won’t change until we change what drives our ideas. The visionary organiser adrienne maree brown wrote not long ago that:

‘We are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced. I believe that we are in an imagination battle.’”

-Rebecca Solnit

If you win the popular imagination, you change the game’: why we need new stories on climate

And as I reflect on what those students taught me, as I watch the “quickening enshittening at 89 seconds to midnight”…

I can’t help but think our most wicked problems share the same obstacle:

a poverty of imagination.

This isn't just a hunch either.

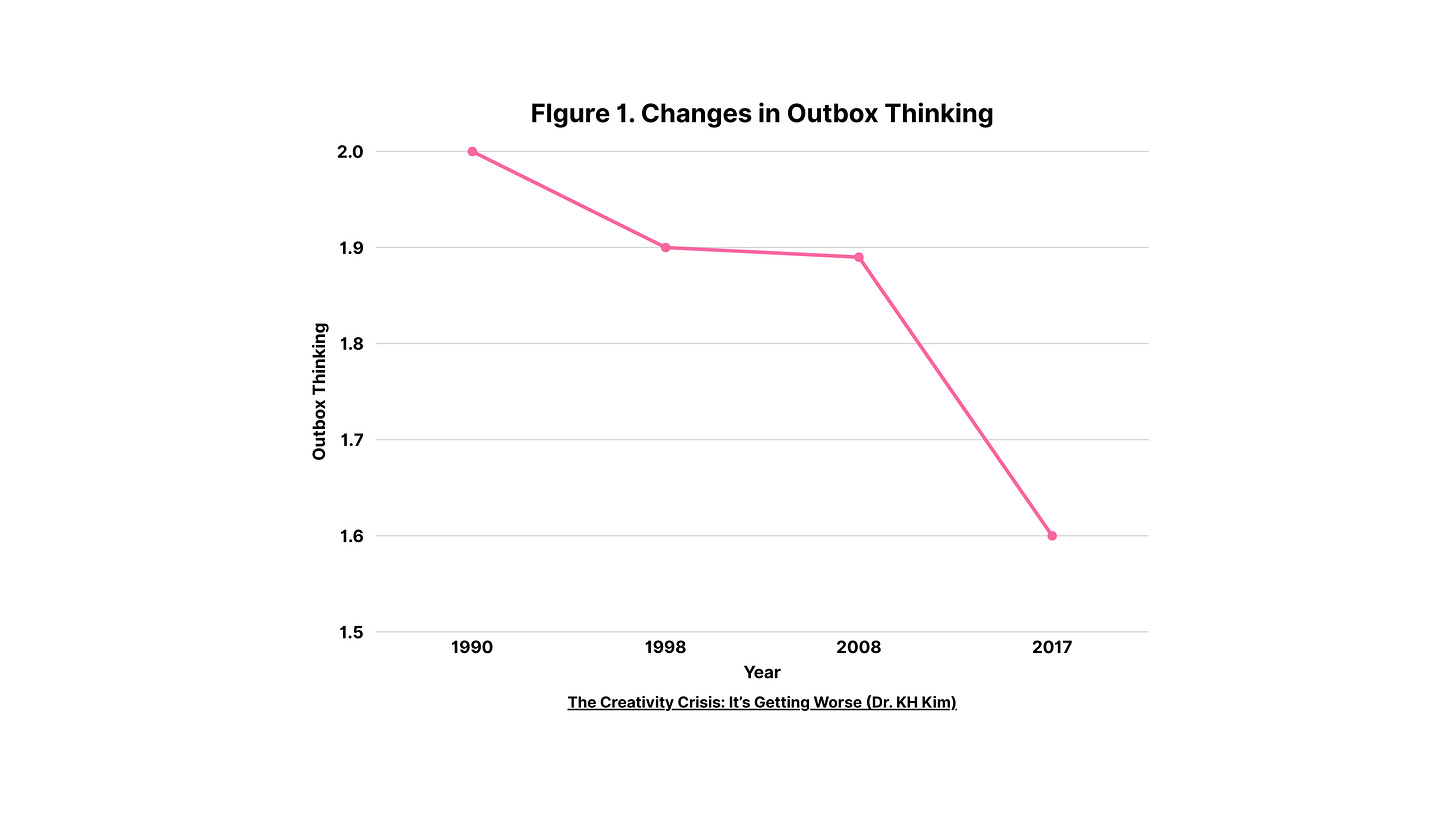

Landmark research analyzing decades of Torrance Test scores—a key measure of creative potential—has documented a significant decline in American creativity, a phenomenon researcher Kyung Hee Kim termed "the creativity crisis”.

We are, as

says, in an imagination battle.And here is something super fucking important we know from movement studies to better illustrate my point:

inspiration + agency = action

Facts and figures and doomscrolling and fear-based messages actually do the opposite.

Those things freeze us. They trigger our survival brain. They’re called action inhibitors.

What moves humans to action is a sense of agency meeting an inspiring, desired possible.

Something to fight for, not against.

And right now the stories we’re really good at telling are about problems and villains.

The stories we’re not as good at telling are about futures worth living in.

And that matters a whole lot when you’re staring down the barrel at not one, not two, but numerous concurrent, compounding and converging existential threats.

But nothing is ever quite that simple — we humans are complex characters after all — so a strange sort of inverse problem happens when we are given one of those rare, powerful stories of futures worth fighting for.

When a vision of a future worth living in is so compelling and too radically different, our underdeveloped imaginative muscle often can't handle it.

We don't just fail to see it; we actively dismiss it as impossible.

The Rubber Band Effect

A perfect example of this happened in 2018, when Black Panther hit theatres. Audiences around the world were captivated by Wakanda — a fictional African nation, never colonized, thriving on the back of advanced science and technology.

Vibranium-powered transit systems, healing beds, holographic communication, sustainable architecture, even social structures designed around reciprocity and stewardship.

It was Afrofuturism on a global stage. For millions of people, it was the first time they saw a vision of Black excellence, technology, and sovereignty woven into a mainstream blockbuster.

And if dollars are a measurement of desire, we are desperate for stories like these. You might even extend that and say we’re desperate for futures like these.

Black Panther’s opening weekend grossed $202M, the fifth highest US box office take in history the year it released.

The other four?

All Sci-Fi: Star Wars (x2), Jurassic World and The Avengers.

Among its many other perhaps more consequential and enduring achievements, Black Panther was a story of a plausible future.

Much of what we saw on screen was real life emerging tech, not pure fantasy.

The CIA — of all unlikely institutions — is one of many high-credibility voices that acknowledged that many Wakandan technologies are based on real science in development. From magnetic levitation trains to energy-harvesting textiles, from nanotech to advanced biomedical devices — these aren’t impossible. They’re emerging.

And yet, because it came to us dressed in Marvel’s cape of “superhero fiction,” (and because racism) most of us unconsciously relegated it to the realm of make-believe.

An inverse design fiction: a vision of futures worth fighting for, dismissed as fantasy precisely because our imaginative muscle is too underdeveloped — and our resistance to difference muscle is too overdeveloped — to take it seriously beyond a few click-bait think pieces.

Again the “poverty of imagination” shows its hand.

When the futures presented are too inspiring, too radical, or too different from the status quo, we can’t stretch to meet them.

Like a rubber band, our mind snaps back to the familiar.

The Rubber Band Effect: The psychological 'snap back' we experience when a radical new idea stretches our worldview.

The initial conflict creates the uncomfortable tension of cognitive dissonance (the stretch). In response, our innate status quo bias acts as the powerful elasticity that pulls our minds back to the familiar, offering the path of least resistance and causing us to dismiss the new paradigm.

This becomes a particularly urgent vulnerability in the age of Artificial Intelligence.

Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin, founders of the

and creators of The Social Dilemma, explain the Rubber Band Effect like this in their talk you should definitely watch called The A.I. Dilemma:There's a very curious experience that that we had trying to explain to reporters what was going on [with A.I.’s development]. So this was January of [2022]. At that point there were maybe a hundred people playing with this like new technology. Now there are, you know, 10 million people having generated over a billion images.

We were trying to explain to reporters what was about to happen and we'd walk them through how the technology worked and that you would type in some text and it would make an image that had never been seen before and they would nod along and at the end they'd be like, ‘cool and what was the image database you got your images from’?

It was just clear that we'd stretched their mind like a rubber band…because this was a brand new capability, a brand new paradigm, their minds would snap back.

And it's not like reporters are dumb. It's a thing that we all experience…we have to expand our minds — and then we look somewhere else — and it snaps back.

Chaos, Speed & Learning The Hard Way

It was early 2023 when they gave this talk citing 10 million daily active AI users. Just over two years later, the landscape has transformed:

There are an estimated 600 million daily active users of generative AI.

The growth from 10M → 600M in roughly two years is a 675% compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

For comparison, the first two years of public internet adoption saw a CAGR of around 90%.

This means AI adoption is moving nearly 8 times faster than internet adoption did.

And consider the depth and degree of transformation the internet already unleashed in only twenty years.

A.I. being born is like the internet being born all over again and we are not recovered from that transformation yet.

This dizzying pace of change is incomprehensible for our brains and largely responsible for the chaotic environment we're all trying to navigate.

Critically, chaos compounds the Rubber Band Effect: when humans encounter stressors like uncertainty, speed, difference and dissonance — dissonance in particular being wildly stressful because we have a deep seated need for our internal reality to match external reality — we will reliably retreat into defensive postures.

Psychology tells us that high stress triggers the 4Fs — fight, flight, freeze, fawn — which shut down the very capacities (creativity, innovation, imagination) we most need.

Extrapolated to the scale of whole societies facing exponential tech change, that defensive posture may not just trip us up, it risks becoming a fatal flaw.

And since I apparently only do life on hard mode, I had to learn all this the hard way.

We Are The Droids We’ve Been Looking For

Doing it ‘the hard way’ looked like a foresight project I took on in late 2023 for a First Nation’s economic development corporation to guide strategic investment decisions.

It was doing that research that I came across the A.I. Dilemma talk and really started to understand the scope, scale and dead ass serious nature of this Fourth Industrial Revolution; this remarkable and historic transformation we’re trying to survive.

The project became sort of like a career capstone where I got to synthesize everything I’ve ever learned into a single deliverable.

I eventually called it The Prosperity Project and will be doing a full lecture on it soon, or you can skip to the good part and sneak peek a super rough cut of the findings, here.

The primary finding, among other juicy discoveries, is that that post-capitalism is already emerging in identifiable ways.

There is a growing chorus of economists, culture analysts and technologists like Tristan Harris saying similarly but we are ultimately still a minority — especially a year ago when I delivered the findings for the first time.

Now take all we’ve covered so far about our atrophied imaginations, and the Rubber Band Effect and our default protective responses and imagine trying to get a bunch of wizened, hardened, cynical board members who believe extractive industries are the only path to wealth; who are deeply conditioned into colonial capitalism’s permanence and inevitability to believe an entire paradigm is collapsing.

Even if they wanted to, they couldn’t.

The Rubber Band Effect conspired with weakened imaginations preventing them from considering the possibility — let alone stretching and snapping in and out of a new paradigm.

And so the first version of the project would sort of ‘fail’, but has in turn become my primary body of work. I stubbornly continued to grow it. It is the north star of everything I will share here at The Permissionless Prof.

And since I’m sort of relentless in trying to realize ideas I’m passionate about, I sat with that first failure for a long time.

I asked a lot of hard questions. The problem wasn't my research or the data; numerous others have seen the work and have confirmed its validity including — and I only mention this for credibility — a Harvard Loeb Fellow.

The former CEO who commissioned the work — who is a visionary and unlike his board, was very ready for this work — just texted about it last week actually:

I hope you don’t mind. I showed a few people your work and they loved it.

So… if people in other contexts ‘love’ the work, what was the problem?

Why was it initially poorly received?

It was poorly communicated and poorly delivered.

It was bad storytelling with insufficient consideration of the resistance the work would face.

That realization left me asking new questions — like how to bridge the gap between the future my research foretold and the present most of us are stuck in.

I forgot the lessons from my students long ago that you need to show, not tell.

Showing is the bridge from the unbelievable to the possible.

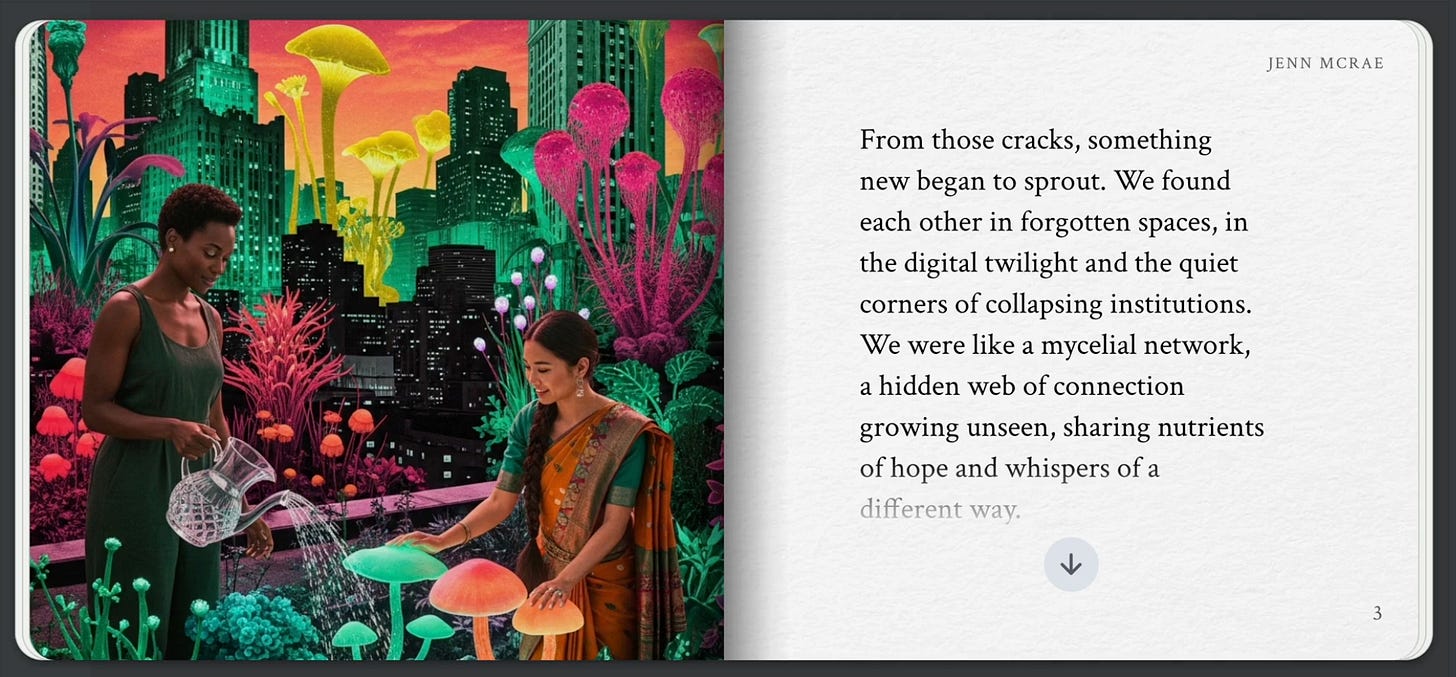

Realizing that, I tried my hand at writing a design fiction of my own, at first just for fun, but with the hope that if it worked out, it could be used in future client work.

Sadly, I haven’t had that opportunity. This entire project got intertwined with a debilitating deterioration of my mental health. I’ve written about that journey at f*ck i love you, so I won’t say a lot here.

But perhaps trying to communicate paradigm transformation wasn’t unrelated to my unraveling.

Perhaps the burden of a mind that can stretch without snapping back is that it might snap forward into an entirely different version of reality instead.

Your Invitation to Design Futures Worth Living In

So, how do you ensure your big idea doesn’t fail? You build a bridge between your vision and the world's reality.

Creating my own design fiction showed me that the materials for that bridge are forged in the imagination; that imagination is strategic and not optional.

It certainly doesn’t have to come at the cost your mental health, either. There are plenty of ways to safely experience alternative realities without entering non-ordinary states of consciousness.

And we have so, so, so many emerging tools to let us show instead of tell, technical experience not required.

For example, a few days ago I logged into Gemini and saw something new in the sidebar: a gem called Storybook. 📖

Curiosity (and ADHD) took over. Ten minutes and a few prompts later I was staring at a fully illustrated, interactive, narrated storybook version of my design fiction. I appended it to the prompt and asked Gemini to adapt it into an adult storybook.

The result was the primary video featured in this post, Futures Worth Living In.

Two years ago we were lucky if we could coax one decent image out of an AI. Today you can spin whole worlds in minutes. Again — the rate of technological progress is beyond most human comprehension.

Which is exactly why tools and practices like design fiction matter.

We can’t change the speed of this transformation. But we can develop our agency to shape it, first and foremost, by strengthening our imagination muscles.

And here’s the loop: design fictions give us a way to practice imagination and bridge that which cannot be seen. The Rubber Band Effect explains why we resist it. And tools like Storybook prove anyone anywhere can start telling stories that galvanize.

Which leads me to my invitation to you: what does your Wakanda look like?

It’s not a rhetorical question either — I want you to try your hand at creating a design fiction. Or trying out some of the exercises form the bonus section below.

Whatever you choose, I want to see what you create. Or hear about the results of what you try. Show me. Report back. Drop links in the comments to what you create. Send files to my DMs.

Better yet, show us — show this growing community of ‘futures designers’ here on Substack.

There’s quite a crew active in this space. See for yourself in Bonus Section 2: Substackers on Futures Worth Living In.

We want you to join us. More accurately, we need you to join us.

This is an all hands on deck situation and it starts with your imagination.

So give it a try. Create your own design fiction.

We’re waiting for you, eager to see the future you’re willing to fight for.

Bonus 1: Resources for Imagined Futures

Here’s a curated list of tools, media, and exercises to help you develop your imaginative muscles, create your own design fictions, and practice seeing the futures you want to build.

AI Storytelling & Worldbuilding Tools 🛠️

These tools have a low barrier to entry and can help you bring ideas to life in minutes.

Gemini Storybook: As mentioned in the essay, this feature within Gemini can turn a simple prompt or an existing text into a narrated, illustrated, interactive story. Perfect for quickly visualizing a narrative.

Leonardo.Ai: An incredibly powerful and user-friendly AI image generator with a generous free tier. Use it to create "artifacts from the future," character concepts, or scenes from the world you're imagining. Image and video generation. It’s what I’m using to create the surreal collage images and videos in these essays (with customization in Canva).

Runway: A leading AI video platform. Its Gen-3 Alpha model can turn text descriptions or existing images into short video clips, allowing you to create cinematic trailers for your imagined futures.

Perplexity AI: Think of this as a "conversational search engine." It's excellent for the research phase of strategic imagination. Ask it speculative questions like, "What are the potential social consequences of a world with universal basic income?" to explore possibilities and their implications.

CustomGPTs: Search ‘speculative design’ or ‘design fiction’ into the GPT marketplace and all kinds of interesting options pop-up.

Books & Foundational Reading 📚

These books provide the mental frameworks for thinking differently about the future.

Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown: A foundational text for anyone interested in social change. It uses nature as a model for how we can be more adaptive, resilient, and collaborative in shaping the future. It is, in essence, a strategic imagination playbook. Also see her resources at the Emergent Strategy Ideation Institute, especially the Toolkit for Cultural Strategy.

Imaginable by Jane McGonigal: Written by a renowned futurist, this book is filled with practical, science-backed exercises and simulations to help you build your imaginative capacity and feel more prepared for any future.

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler: A masterclass in design fiction. Butler doesn't just write about a dystopian future; she creates a new religion, social structure, and survival guide within it, forcing the reader to imagine a different way of being.

Winning the Story Wars by Jonah Sachs: The book mentioned in the essay that explains why compelling, values-driven stories are more critical than ever in our digitally connected world.

Films & Series as Inspiration 🎬

Watch these with a "design fiction" lens. Pay attention not just to the plot, but to the objects, systems, and social norms of the worlds they create.

Arrival (2016): A perfect film about strategic imagination. It explores how radically changing your perspective (in this case, through language) can unlock solutions to seemingly impossible problems.

Her (2013): A quiet, character-driven design fiction that explores the near-future social and emotional consequences of advanced AI companions. It inspired the aesthetic and interaction design of many real-world voice assistants.

Black Mirror (Series): A cautionary anthology series that serves as a powerful reminder that design fiction is also a tool for exploring the unintended—and often dark—consequences of our technological pursuits.

Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022): While not traditional sci-fi, this film is a dazzling exercise in imaginative capacity and empathy, showing how stepping into other possibilities can change how we act in our present reality.

Eternals (2021): This film presents its central characters as the ultimate design fiction practitioners. Sent to Earth millennia ago, their mission is to secretly guide and nurture human civilization by introducing key technologies, myths, and ideas at pivotal moments. The entire arc of human history is reframed as a single, long-term strategic imagination project. It's a powerful story about the intended and unintended consequences of "planting" ideas to shape a world, and the ultimate moral choice of deciding which future is truly worth fighting for. Marvel fans like to hate on this one but I love it!

Practical Exercises ✍️

Try these simple exercises to kickstart your imagination.

The Artifact from the Future: This is the classic design fiction exercise. Imagine a mundane object from the year 2045 (e.g., a coffee cup, a bus ticket, a child's toy, a receipt). What does it look like? What is it made of? What does it tell you about the values, economy, and technology of that world? Sketch it or use an AI image generator to create it, then write a short description.

Backcasting: Instead of forecasting forward, start with a desirable future and work backward. Step 1: Clearly articulate a positive goal for 10 years from now (e.g., "In 2035, my city gets 80% of its energy from community-owned renewables."). Step 2: Ask yourself, "For that to be true, what must have been true in 2032?" Step 3: Repeat the process, working backward to the present day to map out the necessary steps. This turns a dream into a strategy.

The Headlines Game: Quickly imagine and write down three headlines from the front page of a newspaper ten years from now.

One that is wildly optimistic.

One that is deeply pessimistic.

One that is just plain weird. This simple game helps break you out of linear thinking and opens up the range of what you consider possible.

Bonus 2: Substackers for Futures Worth Living In

Just a few days ago,

and I started a database of Substackers who want to connect about Futures Worth Living In.It is inspired by projects like

‘s list of writers interested in the human impacts of AI, and ‘s community.So when I said ‘we’ want you to join us, this is the we who I was talking about.

I was also referring to all the Substackers I feature weekly in f*ck i loved that, my NotebookLM synthesis podcast.

The alumni of these episodes aren’t in the directory yet because that needs consent.

But I do want you to know who they are because, wow. They’re inspiring af and I know I’m only scratching the surface of who’s thinking and writing about this stuff.

Plus this is a chance to make visible who’s in the shared conversation that I see emerging.

So here’s the list of everyone* who’s been a Featured Substacker in the first 10 episodes.

You can also view the full list of featured essays by episode in my Notion database, here.

*apologies for any errors or omissions.

f*ck i loved that Featured Substackers

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , The SFU 2065 creators were a remarkable group I’m very fortunate to have learned with. Kashif Pasta, who played SFU President Shyam Valera went on to become an award winning writer and director whose work has shown at SXSW. Audrey Desjardins (playing incoming student Simone Sanders) is now an associate professor at the University of Washington; Sabrina Hauser (playing Amber Plumeria, Alumna and Entrepreneur) runs an innovation unit at the University of British Columbia; and Mike Funergy (playing Prof. Edward Gesture) runs his own business as a storytelling facilitator. Audrey and Sabrina were also the hybrid student-participatory researchers who co-authored the book chapter referenced in the Origin Story.